This installment of the Middle School Matters Institute Blog focuses on using early warning indicator systems to improve student performance and reduce the risk of future high school dropout.

Contributors:

Doug Elmer, Diplomas Now, Johns Hopkins University (Research Perspective)

Kelsey Lyons Trojacek, School Social Worker, Revere Middle School, Houston Independent School District (Practice Perspective)

The Research Perspective

Over the past decade, educators, researchers, and policymakers have worked together in a concerted effort to increase graduation rates and end the dropout crisis in this country. Although significant progress has been made, far too many students leave the school system before graduating. Nationally, one in five students drops out prior to graduation, with students of color making up a disproportionate number of dropouts across the country. The good news is that through the use of early warning indicator (EWI) systems, educators can accurately identify before high school the students most likely to drop out, empowering teachers and schools to provide supports and interventions to remedy the challenges these students face and to substantially increase the likelihood that they complete high school and move on to postsecondary education.

In recent years, EWI systems have emerged as critical, strategic tools in the effort to ensure that every student remains on track toward a high school diploma and postsecondary opportunities. EWI systems use readily available data to alert teachers and administrators to students who are on the pathway to dropping out. EWI systems grew out of a simple premise—that data could identify students who, absent intervention, were likely to leave the education system. EWI systems guide educators toward the most efficient and effective responses, which include not only student-level interventions, but also classroom, school, and even district actions.

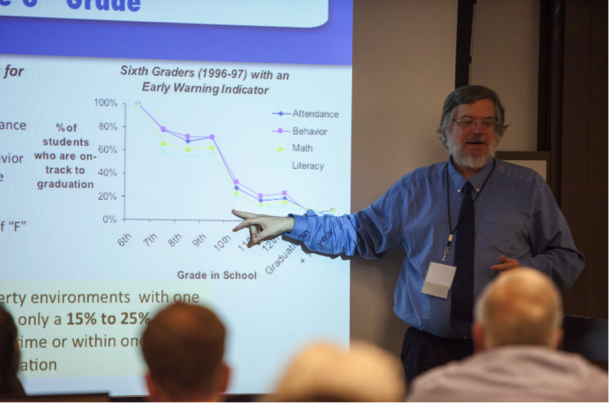

The research behind EWI systems grew out of the larger body of research on dropout prevention and recovery. Researchers noted that a disproportionately small subset of America’s high schools produced the majority of the nation’s dropouts (Balfanz & Legters, 2004) and that performance during the freshman year—particularly with regard to attendance and credit attainment—was closely correlated with high school graduation (Allensworth & Easton, 2005). Researchers at the University of Chicago Consortium (Allensworth & Easton, 2007), Johns Hopkins University, and the Philadelphia Education Fund (Balfanz, Herzog, & Mac Iver, 2007) built on these studies by looking more closely for patterns in longitudinal data and individual student records. Their analysis found that the following three factors—now commonly referred to as the ABC indicators—were the strongest predictors of dropping out:

- Attendance—students who missed more than 20 days of school

- Behavior problems—students who exhibited serious behavior problems (resulting in suspension) or who exhibited persistent, lower-intensity misbehavior, as evidenced by a conduct grade or referrals

- Course failures—students who received a failing grade in language arts or mathematics

Further, the Philadelphia study found that students at risk of dropping out could be identified as early as sixth grade. Since the publication of these initial studies, their findings have been validated many times with state and large district longitudinal studies in Arkansas, Boston, Colorado, Florida, Indianapolis, Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, and Tennessee (Bruce, Bridgeland, Fox, & Balfanz, 2011). More recent studies have demonstrated that districts can identify students at risk of dropping out at nearly any grade level (West, 2013).

The growing body of research validating EWI systems provides several important criteria that effective EWI systems share (Bruce et al., 2011; Mac Iver & Mac Iver, 2009). Districts and schools seeking to launch an EWI system should use these criteria as guideposts during the development phase:

- Build an effective EWI data system: An effective EWI data system provides clear, accurate information around “high-yield” indicators. High-yield indicators—especially attendance, behavior, and course performance—are highly predictive of a majority of dropouts. Although the thresholds for these indicators may vary across districts and states, numerous research studies have confirmed the validity of these primary indicators. EWI data systems should emphasize accuracy over complexity and strive to update data, so that information is as close to real time as possible. All educators, support providers, administrators, and other stakeholders invested in the EWI system should be given appropriate initial and follow-up training and access to the EWI data system.

- Develop a tiered intervention system to respond to EWI data: Although EWI data effectively identify students in need of additional intervention, schools must effectively organize their staff and leverage resources to meet the needs of off-track students. Schools need to engage the “second team” of adults in their school building—counselors, social service providers, tutors, and other student support personnel—in developing a resource map and strategic plan to guide the school’s response to EWI data and use the EWI data to allocate resources and prioritize the work of this team. Further, this team must be integrated with the teaching staff and administration, so that every adult responsible for identifying students in need of support and designing and delivering interventions engages in this work in a coherent, coordinated manner.

- Provide time during the professional day to discuss EWI data as a team: A common trait among districts and schools that effectively use EWI data to develop student interventions and guide school improvement is the creation of common planning time among educators who share groups of students. A common practice among middle schools is to build in common planning time for grade-level teams to analyze EWI data and determine interventions. Schools that effectively use EWI data during common planning times employ a designated facilitator for these discussions, establish protocols for discussion and decision making, and keep careful records of decisions teams make regarding the design and delivery of student interventions. Teachers, administrators, and student support personnel mentioned above are all included in these EWI team meetings, and every team member plays a distinct role within the EWI analysis, intervention delivery, and progress-monitoring process.

Below, Kelsey Lyons Trojacek of Revere Middle School in Houston Independent School District, a Middle School Matters “Tier II” school, shares the school’s experience in establishing an EWI system and the resulting challenges, successes, and lessons learned.

Reflections From the Field

At Revere Middle School, we strive for our students to be Ivy Leaguers, sports stars, scientists, business leaders, inventors, engineers—you name it! However, we noticed too many students becoming ineligible for sports and activities, not enough National Junior Honor Society members, too many average students at risk of not moving on to high school, and unbalanced grade distribution reports. Our campus has amazing teachers and a dedicated staff, so apathy and incompetence were not concerns. But data indicated that our current practices were not preparing students for success. As a result, we began implementing an EWI system to identify and intervene with students on the verge of heading toward failure. Houston Independent School District is a school-of-choice district and has a widespread magnet program. Students may apply to any magnet school, regardless of home address, and transportation is provided with acceptance into the school. These magnet schools have a number of foci: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); energy; law enforcement; aviation; performing arts; business—the list goes on. We want these magnet high schools to want Revere Patriots in their student body, but we have to do our part in getting our kids ready!

Early Warning Indicator System Goals: Changing Our Student Portrait

Our ultimate goal at Revere Middle School is to make school a better place for everyone. In setting up an EWI system and targeting specific student needs, we hoped to reduce discipline referrals, so teachers and administrators could focus their time and energy on instruction, not consequences. Specifically, we set out to do the following:

- Reduce the number of students failing multiple classes (core and elective)

- Reduce the risk of dropout due to behavior, absences, grades, age, and status

- Reduce the number of discipline referrals

- Increase teacher awareness of student needs (personal and educational) and grading practices

Overcoming Obstacles

All systems-level changes must overcome challenges. Our biggest obstacle was the large number of students initially flagged as being at risk. The initial EWI report in our system resulted in more than 75 pages of students!

We had to refine our indicators to generate a more manageable number of target students. This first cohort included (a) every student who was at least 2 years overage and (b) every student who was absent more than 8% of the total school days. We excluded (a) every student who was failing three or fewer classes and (b) every student failing only elective classes. The list of students was still large, so we examined the data for patterns. For instance, we hypothesized that recently immigrated students failed classes because of their limited English proficiency or did not attend school simply because their parents didn’t bring them regularly. This hypothesis prompted us to educate teachers on appropriate accommodations for newly arrived students and to partner with our district’s refugee department to work with parents on educational expectations and concerns in our country.

A second challenge was monitoring intervention effectiveness and following up with teachers in a timely manner. Even though I worked diligently “behind the scenes,” running reports, identifying students at risk, and filling out worksheets designed to give teachers a comprehensive understanding of students’ needs, it was still difficult to keep track of the interventions teachers implemented and how students responded. Meetings occurred every 3 to 6 weeks, but that is long enough to lose documentation or forget exactly what one student’s behavior was like in class several weeks ago. To overcome this obstacle, I kept a copy of each student’s intervention record and asked teachers at the next EWI meeting what interventions they had implemented with each student. This method was effective but time consuming, so we are still piloting different systems.

A third challenge was intervening effectively, so students were no longer at risk. One available support for students was assignment to a school mentor. Many students needed their mentor for longer than 6 weeks, and even with every teacher mentoring two to three students, there often were too many at-risk students for the available resources. This obstacle made supporting new students who would benefit from a mentor even more challenging. Some teachers took on more students, and even a few deans agreed to check in with students. This extra effort helped us reach the top-priority students as best we could.

Our final challenge was realizing that some students would not make progress, despite our best efforts. Teachers worked diligently with students, provided positive reinforcement, involved parents, provided incentives, and created innovative systems and solutions, but—for some students—seemingly to no avail, which is disheartening. We realized we wouldn’t achieve a 100% success rate right away. However, we continue to keep our goal in mind and are hopeful that in time, a student may remember some of the things taught to him or her by our teachers.

Successes

The most rewarding experience was observing changes in the targeted students. Numerous students improved by one or even two letter grades. Student discipline referrals decreased drastically. We observed students who disliked coming to school (and frequent skippers) have a complete change of attitude and begin participating in class regularly. This change affected not only the student, but also the teacher and classroom as a whole.

A second success was the increased communication between teachers. The EWI system included time built into teachers’ busy planning schedules to meet with their team and discuss the targeted students, with support from both administration and support services at the school. During these conversations, we’d commonly hear “I never knew he was going through that…” or “I hadn’t thought of trying that; I’ll do it next time I see her…” Increasing awareness of students’ lives outside of the classroom by communicating with the deans and social workers (our campus doesn’t have counselors) was a benefit for all parties.

From an administrative perspective, a big success was seeing improvement in grade distribution reports. The beginning of the year showed too many students failing classes. When teachers were presented with their grade distribution at every progress report and report card, they could see that too many of their students were failing. Teachers made changes, and the peak of the bell curve started shifting to the right. Deans could review the school’s grading policies, and teachers could examine both their grading procedures and their teaching habits.

Lessons Learned

- Involve school staff members with various perspectives (e.g., teachers, administrators, counselors, nurses). We learned so much about each student just by being in the same room together. By hearing what the nurse says about health, and what the dean says about discipline, and what the social worker says about home life, and what the teacher says about classroom behavior and participation, we could then assemble the puzzle pieces and work together to reach a student.

- Talk to teammates about successes in their classrooms and share successes about building rapport. Through our EWI meetings, we brought teachers together to share strategies that were particularly helpful with specific students who presented a challenge for another teacher. We also identified patterns. Sometimes, teachers who had a student in the morning could tell when that student hadn’t taken his or her medicine, and the social worker could help the family find affordable medication or healthcare. Other times, teachers in the afternoon encountered difficulties with a student and later learned that student didn’t eat lunch that day.

- Dig even deeper than what your EWI report tells you. If a student received 3 days of in-school suspension, ask why. Tardies? Disrespect? Fighting? Target those issues because often, when one thing improves, it has a positive impact on several other things.

- Don’t “pile on” to the teachers’ workload. Frame the work in a positive light. By helping a student, they help their class and their fellow teachers. When assigning mentors, let the teachers choose their mentee students, so that teachers choose students with whom they have a positive relationship.

Learn More

Additional resources on early warning indicator systems are available in the Middle School Matters Clearinghouse. These resources can be further filtered by intended audience or resource type.

References

- Allensworth, E. M., & Easton, J. Q. (2005). The on-track indicator as a predictor of high school graduation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

- Allensworth, E. M., & Easton, J. Q. (2007). What matters for staying on track and graduating in Chicago Public High Schools. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research. Retrieved from http://ccsr.uchicago.edu/publications/what-matters-staying-track-and-graduating-chicago-public-schools

- Balfanz, R., Herzog, L., & Mac Iver, D. J. (2007). Preventing student disengagement and keeping students on the graduation path in urban middle-grades schools: Early identification and effective interventions. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 223–235.

Balfanz, R., & Legters, N. (2004). Locating the dropout crisis. Which high schools produce the nation’s dropouts? Where are they located? Who attends them? (Report 70). Baltimore, MD: Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed at Risk. - Bruce, M., Bridgeland, J. M., Fox, J. H., & Balfanz, R. (2011). On track for success: The use of early warning indicator and intervention systems to build a grad nation. Washington, DC: Civic Enterprises & Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University.

- Mac Iver, M., & Mac Iver, D. (2009). Beyond the indicators: An integrated school-level approach to dropout prevention. Arlington, VA: George Washington University Center for Equity and Excellence in Education.

- West, T. C. (2013). Just the right mix: Using an early warning indicators approach to identify potential dropouts across all grades. Baltimore, MD: Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University.