This month, the Middle School Matters Institute Blog focuses on explicit, research-based vocabulary instruction, including the Frayer Model.

Contributors:

Deborah Reed, Ph.D., Florida Center for Reading Research, Florida State University (Research Perspective)

Priscilla Parhms, Uplift Mighty Preparatory, Uplift Education (Practice Perspective)

The Research Perspective

To read and learn from content area texts, middle school students must have knowledge of two types of vocabulary used in those texts (Townsend, Filippini, Collins, & Biancarosa, 2012). The first might be referred to as general academic terms (e.g., analysis, dissipate). These words have similar or related applications across subject areas and allow us to communicate ideas with greater sophistication and precision, as compared to our casual or conversational language. The other type of vocabulary important for learning in the middle grades is terms specific to particular disciplines (e.g., onomatopoeia, sliding friction). These words are labels for critical processes, literary elements or devices, and concepts that students might not encounter outside of a specific discipline. Even some words that seem familiar, such as grade or mine, have a completely different definition when applied within a content area class.

For successful learning within and across middle grades classes, students must know what these general and discipline-specific academic vocabulary words mean and know how to use them when reading, writing, and orally communicating in class. Students encounter thousands of new words each year, making vocabulary instruction all the more important.

Findings from research (Nagy & Townsend, 2012) suggest that effective vocabulary instruction includes two elements:

- Strategies for learning words independently in the context of text

- Direct teaching of terms that are critical for understanding content area lessons

It is important to note that the latter recommendation, explicitly teaching vocabulary, involves more than the traditional practice of assigning a list of terms at the start of a week or chapter, having students look up the definitions in a dictionary or glossary, and administering a test on the terms at the end of the week or chapter. Rather, explicit instruction that develops students’ academic vocabulary knowledge does the following:

- Offers contextual and pragmatic information to make the words vivid (Vaughn et al., 2009)

- Returns to the terms multiple times throughout a unit of instruction to deepen students’ understanding and reinforce their use of the terms (Lara-Alecio et al., 2012)

- Engages students in discussion about how the terms are used in the text and how they give meaning to the concepts students are learning (Vaughn et al., 2013)

These practices align with Principle 2, Practice 1 of the Reading and Reading Interventions content dimension of the Middle School Matters Field Guide and Research Platform: “Provide explicit instruction of important words.”

The Frayer Model: Background

One instructional activity that combines the above features is referred to as the Frayer Model (Frayer, Frederick, & Klausmeier, 1969). This theoretically derived framework for directly teaching words to support concept development originally had seven steps:

- Give the word and name its relevant attributes.

- Eliminate irrelevant attributes.

- Give examples.

- Give examples of what the word is not (nonexamples).

- List subordinate terms.

- List superordinate terms.

- List coordinate terms.

These steps were a schema for both learning an advanced concept and assessing knowledge of the concept. Early research on the Frayer Model did not involve a graphic organizer, as is commonly used today. Ninth-grade students identified as good and poor readers were randomly assigned to learn social studies content either with the typical textbook lessons or lessons constructed around the Frayer Model steps (Peters, 1974–1975). Results revealed a statistically significant difference in concept comprehension performance, favoring the Frayer Model condition, for good and poor readers alike. This study was not thoroughly described, so it is difficult to determine whether it met more modern quality indicators for experimental research (Gersten et al., 2005).

This original model was later adapted by Graves (1985) for broader use in direct vocabulary instruction. The adaptation reduced the framework to six steps:

- Define the concept and give its essential attributes.

- Distinguish between the concept and similar concepts.

- Give examples and explain why they are examples.

- Give nonexamples and explain why they are nonexamples.

- Ask students to distinguish between other examples and nonexamples given by the teacher and to explain why they are examples or nonexamples.

- Ask students to present their own examples and nonexamples and discuss why they are examples or nonexamples.

This approach was tested with the inclusion of concept webs (graphic organizers that depict relationships between concepts) for learning mathematical vocabulary (Monroe & Pendergrass, 1997). Fourth-graders in the study were randomly assigned to receive only definitional information about the words or to participate in the Frayer Model condition, using the concept webs. Those in the Frayer Model condition recorded significantly more mathematical concepts from their lessons. Although the results are considered promising, the sample size of the study was small (58 students), and no standardized measures of vocabulary or content learning were administered.

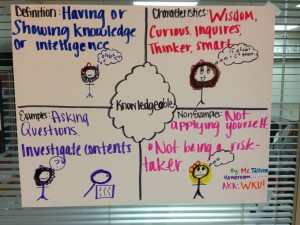

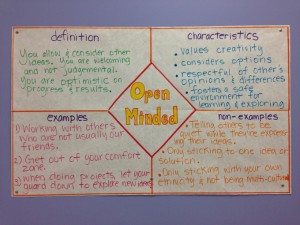

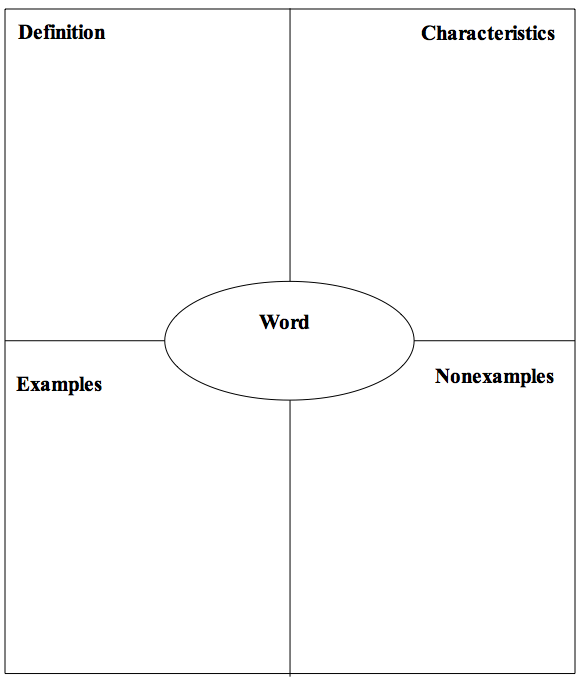

Eventually, the revised six steps of the Frayer Model were incorporated into a four-square graphic organizer (see Figure 1). Despite a wealth of anecdotal reports of its use, no research could be identified that specifically tested this particular format. However, it is consistent with the evidence-based practices for explicit vocabulary instruction outlined earlier as well as with the findings of meta-analyses supporting the use of graphic organizers for students with learning disabilities (Dexter & Hughes, 2011; Gajria, Jitendra, Sood, & Sacks, 2007).

The Frayer Model: Considerations for Use

To be effective, teachers need to be purposeful and deliberate when using the Frayer Model. Not all terms will lend themselves to the kind of multifaceted examination of attributes and applications that are part of the Frayer Model. For example, some terms do not have nonexamples. Others do not have examples that are distinguishable from the characteristics. Teachers need to complete the graphic organizer themselves to determine whether to implement the Frayer Model with a given term. Consistent with the original intent (Frayer et al., 1969), the approach is best when teaching a more complex concept around which many words or related ideas cluster.

In addition, parts of the graphic organizer might be completed iteratively as students build and deepen their conceptual knowledge. At the opening of a unit, perhaps only basic definitional information is provided along with attempts to build background knowledge (upper-left box of Figure 1). As students begin reading, they can look for the characteristics of the term (upper-right box of Figure 1). When they have more experiences with the content and learn related ideas and concepts, students can return to the Frayer Model to provide examples and nonexamples (bottom-left and bottom-right boxes of Figure 1). Throughout the lesson, students need to discuss what they learn and how they think about the information they record on the graphic organizer. This suggested process of teaching with the Frayer Model aligns with the previously discussed evidence-based features of making the terms vivid (Vaughn et al., 2009), returning to the words multiple times throughout a unit of instruction (Lara-Alecio et al., 2012), and fostering discussion about the words and concepts students are learning (Vaughn et al., 2013).

One of the Middle School Matters Institute (MSMI) Tier III schools, Uplift Mighty Preparatory, received a day of professional development focused on effective vocabulary and use of the Frayer Model. Below, Priscilla Parhms shares the school’s experience, successes, challenges, and lessons learned.

Reflections From the Field

In early July, armed with our MSMI Implementation Plan Template, we were ready to plan professional development for the Mighty staff. We had spent 3 awesome days at the MSMI Summer Conference and were ready to share that knowledge with the world. We were confident and excited about our own learning and development. We were prepared.

When we returned to Fort Worth from the MSMI Summer Conference, we spent days developing a basic literacy framework, and we knew explicit vocabulary instruction was a major part of that. There are many things that reading and language experts do not agree on, but teaching vocabulary is not one of them. Vocabulary instruction is an important part of reading and language arts classes, as well as content area classes such as science and humanities. Explicit vocabulary instruction can help students learn the meaning of new words, increase their comprehension, and develop their ability to communicate effectively in a variety of formats. Helping students develop a strong vocabulary increases their capacity to read, write, discuss, present, and think. Vocabulary knowledge is a strong predictor of reading comprehension. To understand text, students must know what most of the words mean.

What we did not anticipate was the vast amount of graphic organizers and models that could be used to teach vocabulary. We reached out to MSMI to lead professional development for our core academic teachers in explicit vocabulary instruction during our scheduled Tier III site visit. With the guidance of Dr. Deborah Reed, we chose the Frayer Model as the strategy that the entire staff would use.

Our Goals

Our major goal at Uplift Mighty is to develop students, putting them on the path to college readiness by the time they enter high school. We needed a common literacy framework that emphasized vocabulary instruction in all content areas and that set the purpose and direction for a balanced and comprehensive literacy program to ensure that all students achieve proficiency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Academic vocabulary and language are critical components of college readiness. Engaging all teachers in professional development to build their capacity to use the Frayer Model to teach vocabulary was another goal. We also wanted to increase our scholars’ trajectory toward college readiness, as measured by the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) and Measures of Academic Progress (MAP).

Our Challenges

Initially, the staff was excited about using the Frayer Model. This initial excitement soon wore off, and teachers went back to teaching vocabulary in myriad ways. We were no longer using a single strategy for vocabulary instruction, causing confusion for scholars and staff alike. We had to remind teachers why it was important to provide repeated exposure to words through an explicit vocabulary instructional strategy. In short, our goal was for the Frayer Model to do the following:

- Help our scholars understand key words and concepts

- Prompt scholars to provide definitions, facts or characteristics, examples, and nonexamples

- Lead scholars to a deeper understanding of words and their relationship to students’ lives

We also soon realized that even though teachers had been trained in using the three categories of words (Tier I, Tier II, and Tier III words), they had a difficult time choosing which words to teach, especially in the content areas.

Teachers also perceived explicit vocabulary instruction as being time consuming, thinking they did not have enough time to use the Frayer Model. We had to refocus teachers on the belief that teaching reading strategies was everyone’s job. We had to continue to work on teaching scholars to become independent vocabulary learners.

Our Success

All scholars on campus have been taught to use the Frayer Model. All core teachers are dedicating part of their class time to explicitly teach academic vocabulary. Making certain that students are familiar with the vocabulary they will encounter in reading selections has made the reading task easier.

As a staff, we have learned to be patient and strategic about which vocabulary words we teach. Teachers provide scholars with repeated exposures to new words in multiple oral and written contexts and sufficient practice sessions.

Our scholars are beginning to learn a range of productive meanings for vocabulary words and the correct way to use those words—beyond simply being able to recognize them in print.

Lessons Learned

- Build a sense of urgency: To nudge teachers out of their comfort zone and help them embrace change, schools must share data to show teachers that the way they previously taught vocabulary was not effective.

- Provide training and ample time: To become knowledgeable and accepting, teachers need multiple opportunities to ask questions, see examples, and practice.

- Chart key behaviors that indicate progress: This charting helps everyone understand the expectations.

- Be patient: Don’t try to do too much too quickly. For example, we started with the English language arts and humanities teachers and branched out to science and mathematics teachers. We then introduced the Frayer Model to our special area teachers, including PE teachers.

- Celebrate early adopters: After completing classroom observations, celebrate teachers who continue to successfully use the Frayer Model.

- Inspect what you expect: When the Frayer Model becomes a priority of the leadership team, it becomes a priority of the staff.

Learn More

To learn more about research-based vocabulary instruction, explore the following resources, organized below by primary audience:

- For middle grades educators and administrators: Frayer Model tips and templates

- For district and state educators: Explicit Vocabulary Instruction in Middle and High School webinar

- For preservice teachers and preservice teacher educators: Teaching Vocabulary and Comprehension in the Content Areas module

- For parents of middle grades students: Vocabulary University website

- For policymakers: What Works Clearinghouse

Additional resources on vocabulary instruction are available in the Middle School Matters Clearinghouse. These resources can be filtered by intended audience or resource type.

References

Dexter, D. D., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Graphic organizers and students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 34, 51–72.

Frayer, D., Frederick, W., & Klausmeier, H. (1969). A schema for testing the level of concept mastery. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Center for Education.

Gajria, M., Jitendra, A. K., Sood, S., & Sacks, G. (2007). Improving comprehension of expository texts in students with LD: A research synthesis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40, 210–227. doi:10.1177/00222194070400030301

Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Compton, D., Coyne, M., Greenwood, C., & Innocenti, M. S. (2005). Quality indicators for group experimental and quasi-experimental research in special education. Exceptional Children, 71, 149–164.

Graves, M. R. (1985). A word is a word . . . or is it? New York, NY: Scholastic.

Lara-Alecio, R., Tong, F., Irby, B. J., Guerrero, C., Huerta, M., & Fan, Y. (2012). The effect of instructional intervention on middle school English learners’ science and English reading achievement. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49, 987–1011. doi:10.1002/tea.21031

Monroe, E. E., & Pendergrass, M. R. (1997). Effects of mathematical vocabulary instruction on fourth grade students. Reading Improvement, 34(3), 120–132.

Nagy, W. E., & Townsend, D. (2012). Words as tools: Learning academic vocabulary as language acquisition. Reading Research Quarterly, 47, 91–108. doi:10.1002/RRQ.011

Peters, C. W. (1974–1975). A comparison between the Frayer Model of concept attainment and the textbook approach to concept attainment. Reading Research Quarterly, 10, 252–254.

Townsend, D., Filippini, A., Collins, P., & Biancarosa, G. (2012). Evidence for the importance of academic word knowledge for the academic achievement of diverse middle school students. Elementary School Journal, 112, 497–518. doi:10.1086/663301

Vaughn, S., Martinez, L. R., Linan-Thompson, S., Reutebuch, C. K., Carlson, C. D., & Francis, D. J. (2009). Enhancing social studies vocabulary and comprehension for seventh-grade English language learners: Findings from two experimental studies. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 2(4), 297–324.

Vaughn, S., Swanson, E. A., Roberts, G., Wanzek, J., Stillman-Spisak, S. J., Solis, M., & Simmons, D. (2013). Improving reading comprehension and social studies knowledge in middle school. Reading Research Quarterly, 48, 77–93. doi:10.1002/rrq.039